Thursday May 28, 2020 By: Dr. Engy Hanna

One day, towards the end of the first century AD and the beginning of the second century AD, thousands of Alexandrians crowded into one of the city’s big theatres. A young man announced the arrival of the famous Greek philosopher and historian Dio Chrysostum, who came to deliver his historic speech, for an hour and a half. Chrysostum criticized the people of the noisy city of Alexandria and their passion for dance and contests, since these shows sometimes led to violence and chaos. In his speech, he mentioned how popular were the dancers and the performers in the Roman theatre and hippodrome. He even quoted the Roman poet Juvenal – describing the passion of Alexandrians for horse-riding, dance and other theatrical arts – calling them “…a folk to whom you need only throw plenty of bread and a ticket to the hippodrome…”

Until the sixth century AD, inhabitants of large cities in Late Antique Egypt were known for their passion for dance and performing arts, as attested in many textual sources from different contexts. Major cities and big towns like Antinoopolis (the modern village of Al-Sheikh Ebada in Minya) and Oxyrhynchus (the modern village of al-Bahnasa), housed many theatres and hippodromes. The scenes of dance, festivals, musicians, tragic pantomime dance, and comic mime shows were common sights in the daily life of urban populations. These scenes were living icons that inspired poets, painters, weavers and sculptors.

Until the sixth century AD, inhabitants of large cities in Late Antique Egypt were known for their passion for dance and performing arts, as attested in many textual sources from different contexts. Major cities and big towns like Antinoopolis (the modern village of Al-Sheikh Ebada in Minya) and Oxyrhynchus (the modern village of al-Bahnasa), housed many theatres and hippodromes. The scenes of dance, festivals, musicians, tragic pantomime dance, and comic mime shows were common sights in the daily life of urban populations. These scenes were living icons that inspired poets, painters, weavers and sculptors.

This passion for performing arts was reflected in visual arts in Late Antiquity (from the third to the seventh century AD). This does not simply reflect the passion of both men and women for dance shows. Rather, the visual representations of dance embedded further underlying social connotations. Following are some messages conveyed through there representations:

Dancers: The Amulets of Victory

In official celebrations, the competition among dancers ignited the enthusiasm of theatre audiences. Circus groups, which undertook the task of organizing the official festivals and theatre shows, organized dance contests for dancers all over the empire. Professional female dancers joined one of four dance factions: the Blues, Greens, Reds or Whites. They were supported by fans, who filled the air in theatre arenas with cheers, shouts and applause. It even seems that fans had representations of their favorite dancers on their personal belongings. This is suggested by a Coptic ivory comb (fig.1), which was excavated from Antinoopolis and is now preserved in the Louvre. The comb is carved in magnificent open work technique with a theatrical scene showing a female mime dancer called Helladia and two other performers. The comb is engraved with an invocation, in which the owner of the comb expresses his/her wish of good fortune for Helladia and her faction, the Blues.

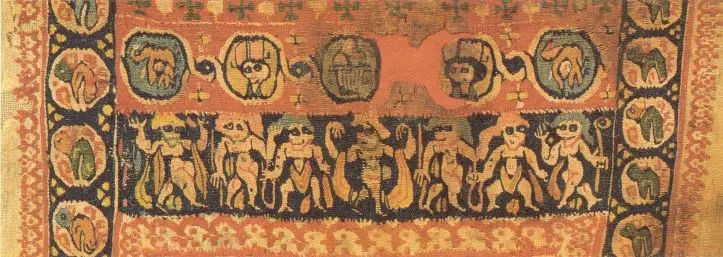

(figs. 2,3)

The enthusiasm of dancers’ supporters all over the empire went even further. Fans appealed to black magic to harm their rivals. Someone put a spell on a dancer from the blue group to lose, requesting the demonic powers to tie the dancer’s neck, hands and feet and to silence the choir and the voices of his fans. Thus, the image of dancers was associated in the minds of the audience with victory and passion. Perhaps for this reason, some Coptic furniture pieces, wall hangings, clothes, and jewellery are decorated with images of dancers wearing victory medallions (figs. 2,3), which were bestowed by emperors and Roman leaders upon victorious dancers. For this reason, dancers were understandably perceived as personifications of the wishes of victory and good fortune.

Dancers: Signs of Good Life

The image of dancers in the thought system of Egyptian society was also associated with well-being and prosperity. At this time, only wealthy families could afford hiring dancers for weddings and family occasions. According to a third-century hiring contract from the village of Philadelphia (the modern village of Kom Al-Kharaba al-Kabir in Al-Fayuum), the average wage of a dancer was 12 drachmae per day. At that time, the wage of a builder was 2 drachmae per day. It is easy to see that hiring dancers, then as now, was a practical way of boasting of, and parading, wealth. On visual media, dancers are frequently depicted while performing under luxurious arcades accompanied by symbols of welfare like baskets of fruit (fig.4).

Dancers: Preachers of Peace

The visual representations of dancers are also interpreted as personifications of peace and salvation. A Coptic tunic (popular dress for both men and women in Late Antiquity) – from the private collection of Rose Choron which is now preserved in the Godwin-Ternbach Museum at Queens College – is decorated with a dance scene showing a troupe of seven dancers: 5 female and 2 male (figs. 5,6).

They are joined by a rope. The male dancers are portrayed facing forward with their feet apart as if doing successive leaps, while the female dancers are crossing one leg over the other and turning their bodies in different directions as if moving through a maze. This composition refers to a well-known dance called “geranos”, a Greek word that means “to wind”. The dance was inspired by a ritual from an ancient Greek myth. It re-enacts the story of the mythological princess Ariadne helping her lover, the god Dionysus, to escape the Labyrinth (a legendary elaborate maze where a mythical monster was believed to live). In the myth, the young people flee to the island of Delos, where they dance hand in hand celebrating their rescue. The geranos dance was popular in the Mediterranean provinces, especially among seafarers, until the twelfth century AD. According to Eustathius, the Archbishop of Thessalonica (1115 – 1195/6), this dance signified peace after war. He viewed the geranos dance as a synthesis of two major forms: a dance of war, represented in the war steps of the male dancers, and a dance of peace, represented in the sensuality of the movements of the female dancers.

In brief, then, the image of dancers in Egyptian society in Late Antiquity was associated with contradictory meanings. As discussed in the previous article, it manifested the meanings of evil, shame, rejection and disgrace as a result of their subversive appearance and performance. But as discussed above, images of dancers conveyed the ideas of victory, prosperity and peace. So was the society’s negative attitude towards dancers a result of actual violation of morality? Was the rhetorical treatment of some aspects of dancers’ lifestyle motivated by particular agendas? Do these two contradictory perspectives reflect the duality of the society? Did contemporaries build their attitude towards dancers’ social class based on individual cases? Did they intentionally exaggerate, using notoriety as a stick to control women’s behaviour? Perhaps the last question holds the key.

More read:

What Coptic Artefacts Tell us About Women in Antique Egypt | Part One

What Coptic Artefacts Tell us About Women in Antique Egypt | Part Two

What Coptic Aretfacts Tell us About Women in Antique Egypt |Part Three

ً Dr Engy Hanna, Lecturer of Coptic Art and Archaeology in Minia University. She completed her Ph.D. at Sussex University in 2017. Her research interests lie in the area of Early Byzantine Art History, more specifically social history, secular art, gender, and sensory perception. Dr Hanna has collaborated actively with staff members at Sussex University. She designed and implemented courses about Coptic Art, Early Christian Art, and Byzantine art history in Egypt and UK. Her book Women in Antique Egypt Through Coptic Art, is available in bookstores.

Dr Engy Hanna, Lecturer of Coptic Art and Archaeology in Minia University. She completed her Ph.D. at Sussex University in 2017. Her research interests lie in the area of Early Byzantine Art History, more specifically social history, secular art, gender, and sensory perception. Dr Hanna has collaborated actively with staff members at Sussex University. She designed and implemented courses about Coptic Art, Early Christian Art, and Byzantine art history in Egypt and UK. Her book Women in Antique Egypt Through Coptic Art, is available in bookstores.

***If you liked this article, don’t forget to subscribe to our newsletter and receive our articles by email.