Sunday April 5, 2020 By: Dr. Engy Hanna

Dancers…Those controversial women of all times, who were secretly loved, publicly hated, the enemies of moral guardians, and the prey of shame-based societies. To the rhythm of their graceful footsteps loving hearts danced, shy faces turned away, and raging tongues flamed. How did they live in the Late Roman period? How were they perceived by society through the lens of shame and honour?

A sixth-century historian once told a story about a holy couple who wandered about disguised as dancers in order to conceal their true identity. When some local noblewoman noticed the beautiful woman in dancers’ dress, she tried to force her to work for her. Surprisingly, the noblewoman’s act was supported by the active collaboration of the local governor. This anecdote was told as a side episode in one of the fifty-eight biographies narrated by the historian John of Ephesus, in his well-known work “Lives of the Eastern Saints.” It supports the assumption that female dancers were a vulnerable class, who were at risk of verbal and physical abuse in full view of the rulers and the common people in all Roman provinces.

A sixth-century historian once told a story about a holy couple who wandered about disguised as dancers in order to conceal their true identity. When some local noblewoman noticed the beautiful woman in dancers’ dress, she tried to force her to work for her. Surprisingly, the noblewoman’s act was supported by the active collaboration of the local governor. This anecdote was told as a side episode in one of the fifty-eight biographies narrated by the historian John of Ephesus, in his well-known work “Lives of the Eastern Saints.” It supports the assumption that female dancers were a vulnerable class, who were at risk of verbal and physical abuse in full view of the rulers and the common people in all Roman provinces.

This phenomenon may have been caused by the Roman laws, which frequently referred to dancers in derogatory terms as a “low” class whose protection was not secured by law. These laws even forbade dancers to dress as nuns or noblewomen in public places, possibly in order to prevent them from concealing their true identity. The vulnerability of dancers could have been also caused by the attitude of politicians and society leaders (like Procopius of Caesarea, the most famous historian of the sixth century), who denounced dancers and portrayed them as a source of evil and “daughters of Satan.” This portrayal was not different from the perception of common people. In the Roman period, if a woman dreamt of herself dancing in public, it was interpreted as a bad omen foreboding a scandal or some other major problem.

This phenomenon may have been caused by the Roman laws, which frequently referred to dancers in derogatory terms as a “low” class whose protection was not secured by law. These laws even forbade dancers to dress as nuns or noblewomen in public places, possibly in order to prevent them from concealing their true identity. The vulnerability of dancers could have been also caused by the attitude of politicians and society leaders (like Procopius of Caesarea, the most famous historian of the sixth century), who denounced dancers and portrayed them as a source of evil and “daughters of Satan.” This portrayal was not different from the perception of common people. In the Roman period, if a woman dreamt of herself dancing in public, it was interpreted as a bad omen foreboding a scandal or some other major problem.

How did Egyptian society in particular perceive dancers at this time?

Few texts from Egypt mention the social perception of dancers, even indirectly. Most of them speak of dancers who practiced their profession in urban cities like Alexandria and Oxyrhynchus (Al-Bahnasa), and the larger villages. To what extent these texts represent dancers all over Late Roman Egypt is not yet known.

An excavated papyrus from the village of Philadelphia (currently known as Kom Al-Kharaba Al-Kabeer in Al-Fayyum) gives a glimpse of the society’s attitude towards dancers. The document is a third-century hiring contract (now preserved in the library archives of Cornell University). The contract shows a wealthy woman named Artemisia arranging for three female dancers to come to the village and perform at a family occasion for six days. The contract sets forth the stipulations of both parties, including wages, accommodation, food, and transportation. It is notable that the hostess of the party pledges to guarantee the safety of the dancers, their costumes, and their gold jewellery during their journey to the village and their stay in her house. The fact that this condition is specifically stated implies that it could not have been taken for granted. While this evidence suggests vulnerability on the part of the dancers, it does not confirm it. What this document and similar sources strongly suggest is that society’s leaders, as well as the common people, viewed women dancers as outsiders who should be despised and excluded. Why?

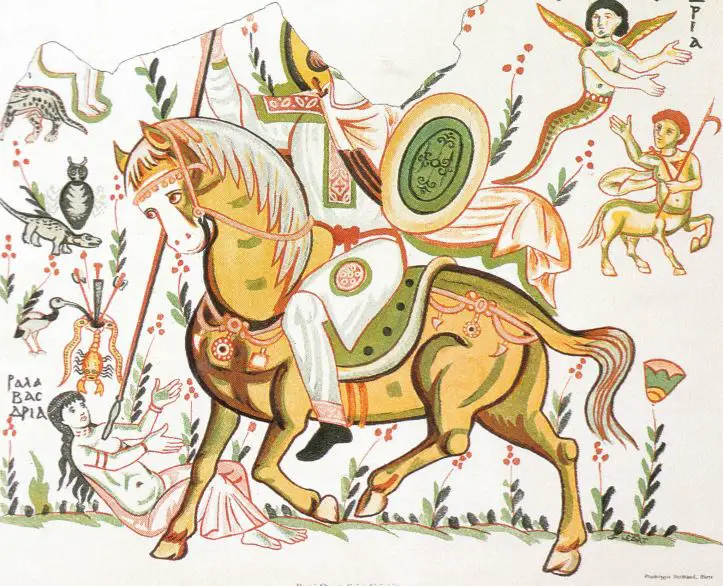

First, dancers’ physical appearance transgressed the social codes of woman’s modesty. They wore transparent clothing, probably made of silk (as suggested by a Roman law), revealing their body underneath (as seen in a portrayal of a crotolla dancer (fig.2) on a Coptic tapestry in the Abegg Stiftung Museum in Bern, Switzerland).

Second, dance performances sometimes involved pagan dramatic content (mimicking stories from Greek mythology), which was regarded by Clergymen as a threat to new Christian believers.

Third, some of the performances mocked clergymen and church rituals.

Fourth, dance performances sometimes transgressed the prevailing codes of morality. Mime shows, for example, used rather blunt language, as suggested by a mime script excavated from Oxyrhynchus (Al-Bahnasa).

In brief, in a society where women were urged to dress and behave modestly, stay at home, be invisible in public places, and subordinate themselves to men and religious institutions, dancers appeared and behaved in a revolutionary manner against traditional morality.

A genius of Coptic art unconsciously expressed the social attitude towards female dancers while portraying the well-known iconography of the holy rider killing a demon. A mural painting at the monastery of St. Apollo at Bawit (fig.3) depicts a saint (probably St. Sissinios) on horseback, driving his lance into the chest of a woman in dancer’s dress. She is identified by an inscription above her head as the goddess Alabasdaria, who was believed to kill fetuses, cause miscarriages, and kill newborns. Replacing the traditional figure of the demon by a beautifully dressed and groomed dancer and associating her with a vicious goddess carried a warning message to onlookers not to accept mimes or dancers socially.

In this blame-filled atmosphere, one might expect that theatres were empty, or that there was no room for dancers in a society built on honor and shame. Surprisingly, reality was different from this “ideal” scene. Various sources with different agendas suggest that dancers enjoyed vast popularity in Roman times, specially in urban areas like Alexandria, to the extent that some rulers had to ban dance shows and contests to guarantee order and stability.

Finally, one may wonder: if female dancers were disdained, why were theatres full of fans? Why were they invited to dance at weddings? Why were clothes, curtains, and toilet boxes decorated with their images? This what I will discuss in the next article.

More read:

What Coptic Artefacts Tell us About Women in Antique Egypt | Part One

What Coptic Artefacts Tell us About Women in Antique Egypt | Part Two

Dr Engy Hanna, Lecturer of Coptic Art and Archaeology in Minia University. She completed her Ph.D. at Sussex University in 2017. Her research interests lie in the area of Early Byzantine Art History, more specifically social history, secular art, gender, and sensory perception. Dr Hanna has collaborated actively with staff members at Sussex University. She designed and implemented courses about Coptic Art, Early Christian Art, and Byzantine art history in Egypt and UK. Her book Women in Antique Egypt Through Coptic Art, is available in bookstores.

Dr Engy Hanna, Lecturer of Coptic Art and Archaeology in Minia University. She completed her Ph.D. at Sussex University in 2017. Her research interests lie in the area of Early Byzantine Art History, more specifically social history, secular art, gender, and sensory perception. Dr Hanna has collaborated actively with staff members at Sussex University. She designed and implemented courses about Coptic Art, Early Christian Art, and Byzantine art history in Egypt and UK. Her book Women in Antique Egypt Through Coptic Art, is available in bookstores.

***If you liked this article, don’t forget to subscribe to our newsletter and receive our articles by email.

This was a great article. Thank you so much for sharing your expertise.

LikeLiked by 1 person

[…] More read: What Coptic Artefacts Tell us About Women in Antique Egypt | Part One What Coptic Artefacts Tell us About Women in Antique Egypt | Part Two What Coptic Aretfacts Tell us About Women in Antique Egypt |Part Three […]

LikeLike