December 21, 2020

By: Alexandra Kinias

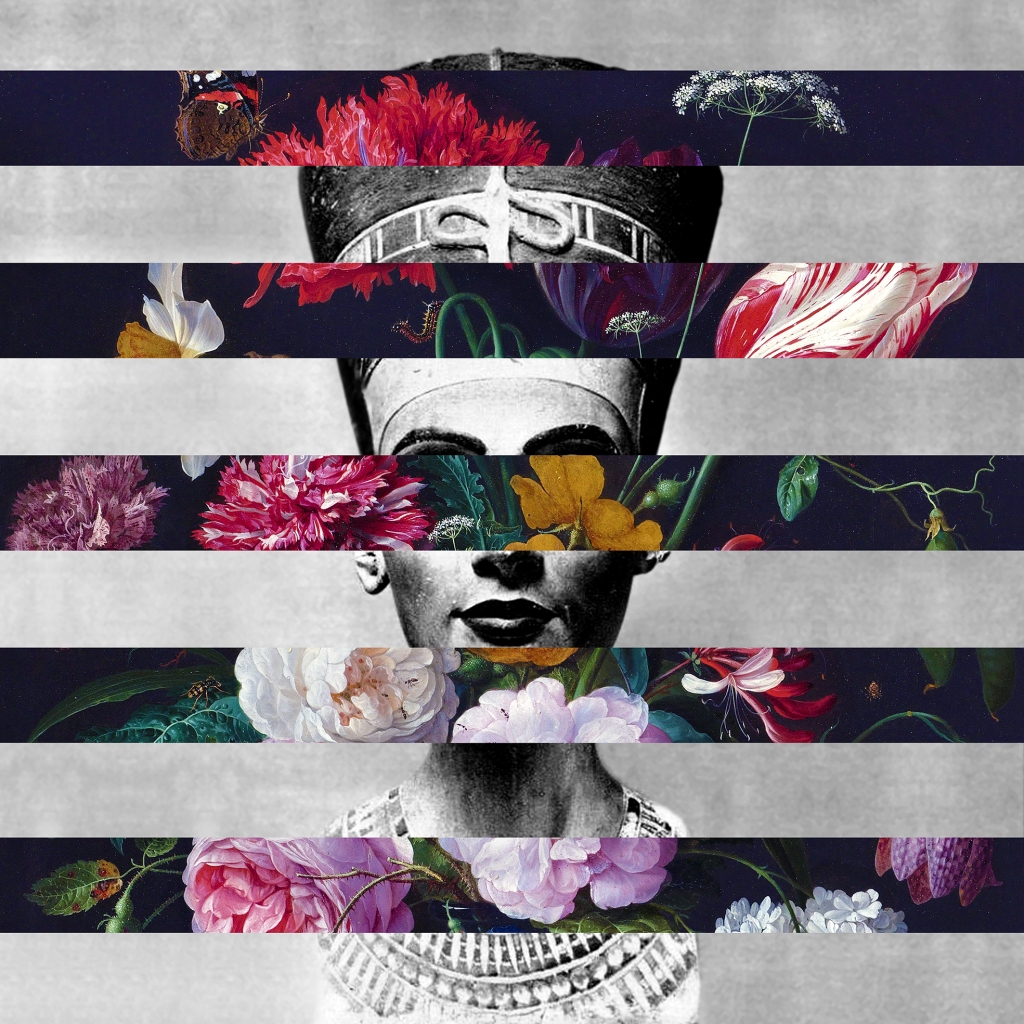

Designer and artist Dina Hafez is best known for her signature style of colorful mixed media pieces that combine craft, digital art, graphic design, and photography. Her work is concerned with feminism from a historic and cultural point of view. It evolves around decolonizing Egyptian History through a feminist lens. Through her art, Dina tries to address the misconception of imposed western narrative that was based on the “orientalist” photography – between mid 1800s to early 1900s. During these 100 years, photography was exclusive to a handful to western male photographers whose objective was to sell a staged notion of Egypt to tourists.

Dina works to alter this representation and take ownership of the photographic archival material Egypt has for this period. She worked on three projects so far. The most recent she completed is “Women Ascending the Pyramid”, in which she replaces white men with Egyptian women.

Her passion for playing with beads as a child developed and evolved over the years to become one of the materials she uses today to create some of her art pieces, inspired by and aimed to preserve the Egyptian heritage. Her third project is built upon her childhood hobby. She named it Unfamiliar Faces, an exhibition of seven portraits of anonymous Egyptian women. Through luring in the spectacle with colorful design and shiny beads, she seeks to question the connection of Egyptians to their heritage and how they relate to it.

Another project in progress is called “My Name Is”, where she gives names and create life stories to anonymous women in vintage photographs.

Dina has a BA from the American University in Cairo and an MA in Arts and Heritage Management from Maastricht University, the Netherlands. She has been exploring notions of identity, decolonization, and feminism through art and craft for over three years. Currently, she is a specialist working on some of Egypt’s largest cultural heritage preservation projects. Dina is also a wife, a mother, and an entrepreneur of the lifestyle brand for textiles and home accessories Zahya Artisanal.

WoE: Can you tell us more about the series ‘My Name Is’, and how from your POV it is going to reclaim our heritage?

Dina Hafez: ‘My Name Is’ series seeks to acknowledge the existence of these women [in vintage black and white photos] by simply giving them names. When people ascribe faces to names, the women in the pictures transform from being “objects” in an image to “human beings” with stories. I hope whoever comes across the pieces would think of the women as someone they might relate to from the past. These women lived on this same land, had families and friends. They were someone’s mother, sister, or wife who had hopes and dreams, and I’m sure they would have loved for their photographs to be recognized.

This in my opinion contributes to reclaiming part of heritage which is often told by westerners. You reclaim something by taking ownership, by telling your own narrative of the story, by not being a passive recipient of whatever is told or given to you. I work with these photographs because I want to, because I can and because they are part of my history as an Egyptian. This sense of entitlement has not always been there for me, it’s a process, and when you get there it feels liberating to finally take matters in your hands (literally and figuratively).

As a craftswoman, I take pride in working with my hands on the pieces I make. The medium is the message as they say. Craft has been dismissed from the art world for being a “woman’s thing”. In Egypt, there is a growing interest in contemporary craft. We have a long history with craft in general, but as a modern maker I’m more concerned with innovating traditional techniques and applications of crafts and materials.

WoE: Can you explain how Egyptian heritage was lost because of colonization?

DH: Egyptian heritage has been colonized for so long, it might still be, at least partially. Coloniality is in many different ways more present than past. Initially, decolonization referred to the process former colonies underwent to free themselves of the colonial supremacy. Today the term has become much more than that: a philosophical, moral, social, spiritual and also activist call that points to the fact we are still subject to the ideology of colonialism. The notion of “who’s heritage is it?”, who takes the decision of what’s heritage and what’s not, who determines how we contribute to a renewal of the canon with stories and reference frames that have been systematically erased from it? These are all questions that are not exclusive to the Egyptian context and are shared on a global level. However, the discussion in Egypt is limited to only few, for many reasons which are beyond the scope of this article. In short, I believe it’s a good start to ask questions and not necessarily have the answers. How do we change the focus, how do we alter our perspective? Creating dialogue at this stage is the way to move forward to involve all members of the community. Art is one of the ways to trigger people’s curiosity and create room for multiple perspectives and narratives.

WoE: Why do you think photographers at the turn of the century were fascinated with the women of the East?

DH: In the second half of the nineteenth century there had been a growing interest in the Middle East in general and specifically for Egypt, Morocco, Syria, and Jerusalem. It’s the west’s fascination with the “other”, the “exotic”. Foreign photographers fed this frenzy through what’s called “orientalist photography.” In Egypt, we had the Greek Brothers Zangaki, the Frenchmen Félix Bonfils and Emile Bechard, the Italians Antonio Beato and Luigi Fiorillo, and the Turk of Kurdish ancestry Pascal Sébah. Their photographs were aimed at a particular clientele: the growing number of European and American tourists visiting Egypt. With few exceptions for Fiorillo’s work, the photographs from that time weren’t concerned with documentation as much as it was for commercial consumption. Almost all of the photos were staged, whether in studios or outdoor.

The photographers depictions of life during that time magnified cliches that offend me as an Egyptian and as a woman. The major misinterpretation I’m concerned with is the portrayal of Egyptian women. The photographs lacked any depth or true meaning to the lives of Egyptian women at the time. Women were merely props on a stage. They were either sexualized to serve fantasies of the “harem” to the west, or, they were portrayed as exotic objects dressed up in traditional clothing and structured to pose mysteriously behind a mashrabeya or a veil. It’s important to mention women were not allowed to interact with stranger men, let alone foreign photographers. That’s why a photographer had to resort to his imagination.

It’s easy to fall for the allure of these vintage photographs and get lost in reminiscent nostalgia. That’s why I find it crucial to encourage people to engage critically with such photographs. It’s fine to be romantic about mashrabeyas and donkey carts as long as one is aware of the full picture not only what is captured in that moment.

WoE: Why do you think some people lost touch with their roots, and there are even making an effort to alienate themselves entirely in favor to other western cultures? How can this be reversed?

DH: There are two teams when it comes to roots and identity in a neo-globalized world. One team argues that the more globalized we become, the more we’d want to fit in and our infatuation with the west would ultimately lead us to abandon our culture and traditions and become “a global citizen”. The other team stands for the opposite, which means the more we’re faced with globalization the more we retreat to our heritage and traditions to root us. I’m for a balance between these two push and pull forces. Adaptation is important to survival. So is a clear understanding of who we are and where we come from. I think of roots as souls. It’s a distinction to our individuality. I take great pride of being Egyptian. My own interpretation of what “Egyptian” means is completely up to me. I’m grateful to belong to such a country with rich history and immense cultural heritage. I celebrate this across all the designs I make. Whether it’s a cushion or an artwork, they do tell a story and start a conversation.

Back in 2011, when I started making designs with pictures of ancient Egypt or modern history, some of my friends told me “but there aren’t any tourists now. Who’s going to buy your work?” It really shocked me because I never had tourists as my primary target. My work is first and foremost for Egyptians. And that’s what I seek to change, the idea that our heritage is not ours. We’ve become very distant and alienated from our past that we think of it as commodity for others. I’ve been selling my pieces ever since and most of my clients are Egyptians. Nothing brings me more joy than when people start opening up to new perspectives and possibilities. Counterintuitive to the common understanding, heritage is not primarily about the past – it is about the present. Heritage harnesses the power of the past to lay foundation of present social and cultural relations.

View Dina Hafez art collection on her Instagram here

***If you liked this article, don’t forget to subscribe to our newsletter and receive our articles by email.